- Home

- Actividades

- Ciudadanía Americana

- Comunismo

- Economía

- Estadidad

- Estudios

- "La Gran Potencia Del Caribe" – Bernardo Vázquez

- All Politics Is Local – Tip O'Neill

- Anotaciones Para La Campaña

- Citizenship In The American Empire – Cabranes

- Cómo Ganar Elecciones – Napolitan

- Creación del PNP

- Documentos Históricos de Puerto Rico

- El Arte de la Guerra – Sun Tzu

- El Príncipe de Maquiavelo

- Filosfía Politíca

- Historia de los Partidos Políticos de PR – Bolívar Pagán

- La Retranca del ELA – Dávila Colón

- Los Protocolos De Los Sabios – Parodia Política

- Memorias del Amolao

- On the Nature of War – Clausewitz

- Slogans

- UN MENSAJE A GARCIA

- FashionClothingshirt

- general

- Historia

- No lo Hagan

- Política

- Anotaciones para la Campaña Estadista – Pompy González

- Campaña

- Candidatos

- Comentarios Diarios de Actualidad

- Corupción

- Deportes

- Economía

- Educación

- Izquierdistas

- Justicia

- Links Pro-Americanos

- Mala Administración PPD y Neo-Comunistas

- Municipios y Precintos

- Neo-Comunistas

- PIP

- PIP – Escritos y Noticias

- PNP

- PNP – Escritos y Noticias

- Pobreza

- Política en Latinoamérica

- PPD

- PPD – Escritos y Noticias

- Retiro

- Salud

- Seguridad

- Status

- Trabajo

- Salud

- Seminarios

- Status

- Videos

- Voluntarios Estadistas

- Vídeos

- Indices – Libros y Links Estadistas

- Lucha E51

- UNETE A: @EstadoPRUSA seminarios-pnp.com

- Libros de Estrategia y Campaña Política

- Temas

- Tertuliando

- «Sin Miedo» gritan los Dirigentes Populares que tienen Miedo

- Temas Estadistas Actuales Para Tertulias y Actividades

- Líderes de la Estadidad

- Gobierno publica estados financieros auditados del 2022 y anuncia pasos para regresar a los mercados

- My Calendar

- No debe ocurrir una primaria Novo progresista – Por Dr. José M. Saldana

- Defendiendo la Rectora de la Escuela de Medicina – O Separatistas la Destruyen

- Cuatro libros indispensables – Por Mario Ramos Méndez – Historiador

- Pierluisi y el Desarrollo Económico Logrado Mejor Que muchas Décadas

- Sobre las candidaturas de agua – Por Iván Rivera

- El nacimiento e influencias revolucionarias del Movimiento Pro-Independencia de Puerto Rico – Por Mario Ramos Méndez

- La corrupción que no tiene fin – Por Mario Ramos Méndez

- Realidad Colonial: Lucha entre Biden y Trump – Por Dr. José M. Saldaña

- La isla de los piratas – PorMario Ramos Méndez, Historiador

- Ya es hora de actuar localmente pues Trump continúa prevaleciendo en las primarias – Por Dr. Jos’e M. Saldaña

- Pedro Pierluisi Incansable por Puerto Rico

- Si los Americanos nos Hacen Iguales es la Mejor Independencia – De Diego

- Muñoz y el sueño derrotado – Por Mario Ramos Méndez

- ¿Que es la estadidad? – Jerry Acosta

- Estadistas Ganan Posiciones en Votaciones Partido Demócrata – marzo 2024

- Los Separatistas Comunistoides

- La nueva secretaria de Educación – Por Mario Ramos

- La Próxima Y Severa Crisis Por Venir! – Minoria de Uno

- LA CUARTA REVOLUCION INDUSTRIAL Y SUS EFECTOS!

- Página Pedro Pierluisi y Para el Voto Ausente y Adelantado

- Santa Cló como tradición puertorriqueña – Mario Ramos Méndez 22/12/2023

- No El voto extranjero en el P. de la C. 1891 – Por Andrés L. Córdova

- Pierluisi y el Desarrollo Económico Logrado Mejor Que muchas Décadas

- La Estadidad para Puerto Rico más Cerca que Nunca

- #82558 (sin título)

- Comparación Económica Estados y Puerto Rico – 2020

- Para el PN P Ganar Cada Municipio

- Programa Federal Instalar Paneles Solares

- ¿Somos viables como pueblo?

- La decisión del gobernador sobre LUMA

- Convocan a manifestaciones en contra de la estadidad y a favor de la descolonización Publicado el junio 20, 2021 por estado51prusa

- Puerto Rico’s ‘Tax Haven’ Isn’t Causing Inequality, Its Territorial Status Is

- SILA Calderón opinando – Por José M. Saldaña

- PNP le contesta al PIP: “tenemos mandato del Pueblo”

- ¿Que es la estadidad? – Jerry Acosta

- Nacionalismo? Por Mario Ramos

- 2019 Presidential candidates discovering Puerto Rico – Por Kenneth McClintock

- La Realidad Cubana que Victoria Ciudadana Aspira

- Amplio Respaldo USA a la Estadidad para ZpR

- El vínculo indisoluble de la ciudadanía americana

- Estado51PRUSA-Blog

- “Tienen una carga importante de trabajo”, dice Pierluisi sobre la nómina de confianza del DE

- Sobre la Asamblea Demócrata, las Primarias del PNP y el 2024!

- Integrarán más personas con diversidad funcional en el gobierno

- Pierluisi: «Por cada Crítica Hay Cientos de Obras»

- Solicitudes de voto adelantado ya están disponibles en el PNP

- Una agenda ideológica – Por Mario Ramos Méndez

- Pierluisi afirma que «este no es el momento» para convocar un plebiscito de estatus

- Trump criticizes Biden’s treatment of Puerto Rico – The San Juan Star

- Amigo de JGo dice que fue «inducida a error» al aspirar por la gobernación

- SALIDA SUMARIA DE LA MARINA DE PUERTO RICO

- NO TE DEJES CONFUNDIR DILE NO A LA NACIÓN VIRTUAL

- Oreste Ramos Lee la columna de opinión de Mario Ramos Méndez

- La agresora corrupción – Lee la columna de opinión de Mario Ramos Méndez aquí

- Los estadistas independientes – Por Mario Ramos Méndez

- Contáctanos

Conoce a Alaska y Divulga su Historia – Estadidad Mil Veces Mejor

Alaska

| [show]Alaska state symbols |

|---|

Alaska (![]() i/əˈlæskə/) is a U.S. state located in the northwest extremity of North America. The Canadian administrative divisions of British Columbia and Yukon border the state to the east; its most extreme western part is Attu Island; it has a maritime border with Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. To the north are the Chukchi and Beaufort seas–the southern parts of the Arctic Ocean. The Pacific Ocean lies to the south and southwest. Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area, the 3rd least populous and the least densely populated of the 50 United States. Approximately half of Alaska’s residents (the total estimated at 738,432 by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2015[2]) live within the Anchorage metropolitan area. Alaska’s economy is dominated by the fishing, natural gas, and oil industries, resources which it has in abundance. Military bases and tourism are also a significant part of the economy.

i/əˈlæskə/) is a U.S. state located in the northwest extremity of North America. The Canadian administrative divisions of British Columbia and Yukon border the state to the east; its most extreme western part is Attu Island; it has a maritime border with Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. To the north are the Chukchi and Beaufort seas–the southern parts of the Arctic Ocean. The Pacific Ocean lies to the south and southwest. Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area, the 3rd least populous and the least densely populated of the 50 United States. Approximately half of Alaska’s residents (the total estimated at 738,432 by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2015[2]) live within the Anchorage metropolitan area. Alaska’s economy is dominated by the fishing, natural gas, and oil industries, resources which it has in abundance. Military bases and tourism are also a significant part of the economy.

The United States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire on March 30, 1867, for 7.2 million U.S. dollars at approximately two cents per acre ($4.74/km2). The area went through several administrative changes before becoming organized as a territory on May 11, 1912. It was admitted as the 49th state of the U.S. on January 3, 1959.[5]

Etymology

The name «Alaska» (Аляска) was introduced in the Russian colonial period when it was used to refer to the peninsula. It was derived from an Aleut, or Unangam idiom, which figuratively refers to the mainland of Alaska. Literally, it means object to which the action of the sea is directed.[6][7][8]

Geography

Alaska is the northernmost and westernmost state in the United States and has the most easterly longitude in the United States because the Aleutian Islands extend into the Eastern Hemisphere. Alaska is the only non-contiguous U.S. state on continental North America; about 500 miles (800 km) of British Columbia (Canada) separates Alaska from Washington. It is technically part of the continental U.S., but is sometimes not included in colloquial use; Alaska is not part of the contiguous U.S., often called «the Lower 48». The capital city, Juneau, is situated on the mainland of the North American continent but is not connected by road to the rest of the North American highway system.

The state is bordered by Yukon and British Columbia in Canada, to the east, the Gulf of Alaska and the Pacific Ocean to the south and southwest, the Bering Sea, Bering Strait, and Chukchi Sea to the west and the Arctic Ocean to the north. Alaska’s territorial waters touch Russia’s territorial waters in the Bering Strait, as the Russian Big Diomede Island and Alaskan Little Diomede Island are only 3 miles (4.8 km) apart. Alaska has a longer coastline than all the other U.S. states combined.[9]

Alaska’s size compared with the 48 contiguous states. (Albers equal-area conic projection)

Alaska is the largest state in the United States in land area at 663,268 square miles (1,717,856 km2), over twice the size of Texas, the next largest state. Alaska is larger than all but 18 sovereign countries. Counting territorial waters, Alaska is larger than the combined area of the next three largest states: Texas, California, and Montana. It is also larger than the combined area of the 22 smallest U.S. states.

Regions

There are no officially defined borders demarcating the various regions of Alaska, but there are six widely accepted regions:

South Central

The most populous region of Alaska, containing Anchorage, the Matanuska-Susitna Valley and the Kenai Peninsula. Rural, mostly unpopulated areas south of the Alaska Range and west of the Wrangell Mountains also fall within the definition of South Central, as do the Prince William Sound area and the communities of Cordova and Valdez.[10]

Southeast

Also referred to as the Panhandle or Inside Passage, this is the region of Alaska closest to the rest of the United States. As such, this was where most of the initial non-indigenous settlement occurred in the years following the Alaska Purchase. The region is dominated by the Alexander Archipelago as well as the Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the United States. It contains the state capital Juneau, the former capital Sitka, and Ketchikan, at one time Alaska’s largest city.[11] The Alaska Marine Highway provides a vital surface transportation link throughout the area, as only three communities (Haines, Hyder and Skagway) enjoy direct connections to the contiguous North American road system.[12] Officially designated in 1963.[13]

Interior

Denali is the highest peak in North America.

The Interior is the largest region of Alaska; much of it is uninhabited wilderness. Fairbanks is the only large city in the region. Denali National Park and Preserve is located here. Denali is the highest mountain in North America.

Southwest

Grizzly bear fishing for salmon at Brooks Falls, part of Katmai National Park and Preserve.

Southwest Alaska is a sparsely inhabited region stretching some 500 miles (800 km) inland from the Bering Sea. Most of the population lives along the coast. Kodiak Island is also located in Southwest. The massive Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta, one of the largest river deltas in the world, is here. Portions of the Alaska Peninsula are considered part of Southwest, with the remaining portions included with the Aleutian Islands (see below).

North Slope

The North Slope is mostly tundra peppered with small villages. The area is known for its massive reserves of crude oil, and contains both the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska and the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field.[14] Barrow, the northernmost city in the United States, is located here. The Northwest Arctic area, anchored by Kotzebue and also containing the Kobuk River valley, is often regarded as being part of this region. However, the respective Inupiat of the North Slope and of the Northwest Arctic seldom consider themselves to be one people[citation needed].

Aleutian Islands

More than 300 small volcanic islands make up this chain, which stretches over 1,200 miles (1,900 km) into the Pacific Ocean. Some of these islands fall in the Eastern Hemisphere, but the International Date Line was drawn west of 180° to keep the whole state, and thus the entire North American continent, within the same legal day. Two of the islands, Attu and Kiska, were occupied by Japanese forces during World War II.

Natural features

Augustine Volcano erupting on January 12, 2006

With its myriad islands, Alaska has nearly 34,000 miles (54,720 km) of tidal shoreline. The Aleutian Islands chain extends west from the southern tip of the Alaska Peninsula. Many active volcanoes are found in the Aleutians and in coastal regions. Unimak Island, for example, is home to Mount Shishaldin, which is an occasionally smoldering volcano that rises to 10,000 feet (3,048 m) above the North Pacific. It is the most perfect volcanic cone on Earth, even more symmetrical than Japan’s Mount Fuji. The chain of volcanoes extends to Mount Spurr, west of Anchorage on the mainland. Geologists have identified Alaska as part of Wrangellia, a large region consisting of multiple states and Canadian provinces in the Pacific Northwest, which is actively undergoing continent building.

One of the world’s largest tides occurs in Turnagain Arm, just south of Anchorage – tidal differences can be more than 35 feet (10.7 m).[15]

Alaska has more than three million lakes.[16] Marshlands and wetland permafrost cover 188,320 square miles (487,747 km2) (mostly in northern, western and southwest flatlands). Glacier ice covers some 16,000 square miles (41,440 km2) of land and 1,200 square miles (3,110 km2) of tidal zone. The Bering Glacier complex near the southeastern border with Yukon covers 2,250 square miles (5,827 km2) alone. With over 100,000 glaciers, Alaska has half of all in the world.

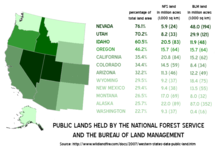

Land ownership

Alaska has more public land owned by the federal government than any other state.[17]

According to an October 1998 report by the United States Bureau of Land Management, approximately 65% of Alaska is owned and managed by the U.S. federal government as public lands, including a multitude of national forests, national parks, and national wildlife refuges.[18] Of these, the Bureau of Land Management manages 87 million acres (35 million hectares), or 23.8% of the state. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. It is the world’s largest wildlife refuge, comprising 16 million acres (6.5 million hectares).

Of the remaining land area, the state of Alaska owns 101 million acres (41 million hectares), its entitlement under the Alaska Statehood Act. A portion of that acreage is occasionally ceded to organized boroughs, under the statutory provisions pertaining to newly formed boroughs. Smaller portions are set aside for rural subdivisions and other homesteading-related opportunities. These are not very popular due to the often remote and roadless locations. The University of Alaska, as a land grant university, also owns substantial acreage which it manages independently.

Another 44 million acres (18 million hectares) are owned by 12 regional, and scores of local, Native corporations created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971. Regional Native corporation Doyon, Limited often promotes itself as the largest private landowner in Alaska in advertisements and other communications. Provisions of ANCSA allowing the corporations’ land holdings to be sold on the open market starting in 1991 were repealed before they could take effect. Effectively, the corporations hold title (including subsurface title in many cases, a privilege denied to individual Alaskans) but cannot sell the land. Individual Native allotments can be and are sold on the open market, however.

Various private interests own the remaining land, totaling about one percent of the state. Alaska is, by a large margin, the state with the smallest percentage of private land ownership when Native  corporation holdings are excluded.

corporation holdings are excluded.

Climate

Köppen climate types of Alaska.

The climate in Southeast Alaska is a mid-latitude oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb) in the southern sections and a subarctic oceanic climate (Köppen Cfc) in the northern parts. On an annual basis, Southeast is both the wettest and warmest part of Alaska with milder temperatures in the winter and high precipitation throughout the year. Juneau averages over 50 in (130 cm) of precipitation a year, and Ketchikan averages over 150 in (380 cm).[19] This is also the only region in Alaska in which the average daytime high temperature is above freezing during the winter months.

The climate of Anchorage and south central Alaska is mild by Alaskan standards due to the region’s proximity to the seacoast. While the area gets less rain than southeast Alaska, it gets more snow, and days tend to be clearer. On average, Anchorage receives 16 in (41 cm) of precipitation a year, with around 75 in (190 cm) of snow, although there are areas in the south central which receive far more snow. It is a subarctic climate (Köppen: Dfc) due to its brief, cool summers.

The climate of Western Alaska is determined in large part by the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska. It is a subarctic oceanic climate in the southwest and a continental subarctic climate farther north. The temperature is somewhat moderate considering how far north the area is. This region has a tremendous amount of variety in precipitation. An area stretching from the northern side of the Seward Peninsula to the Kobuk River valley (i. e., the region around Kotzebue Sound) is technically a desert, with portions receiving less than 10 in (25 cm) of precipitation annually. On the other extreme, some locations between Dillingham and Bethel average around 100 in (250 cm) of precipitation.[20]

The climate of the interior of Alaska is subarctic. Some of the highest and lowest temperatures in Alaska occur around the area near Fairbanks. The summers may have temperatures reaching into the 90s °F (the low-to-mid 30s °C), while in the winter, the temperature can fall below −60 °F (−51 °C). Precipitation is sparse in the Interior, often less than 10 in (25 cm) a year, but what precipitation falls in the winter tends to stay the entire winter.

The highest and lowest recorded temperatures in Alaska are both in the Interior. The highest is 100 °F (38 °C) in Fort Yukon (which is just 8 mi or 13 km inside the arctic circle) on June 27, 1915,[21][22]making Alaska tied with Hawaii as the state with the lowest high temperature in the United States.[23][24] The lowest official Alaska temperature is −80 °F (−62 °C) in Prospect Creek on January 23, 1971,[21][22] one degree above the lowest temperature recorded in continental North America (in Snag, Yukon, Canada).[25]

The climate in the extreme north of Alaska is Arctic (Köppen: ET) with long, very cold winters and short, cool summers. Even in July, the average low temperature in Barrow is 34 °F (1 °C).[26] Precipitation is light in this part of Alaska, with many places averaging less than 10 in (25 cm) per year, mostly as snow which stays on the ground almost the entire year.

| Location | July (°F) | July (°C) | January (°F) | January (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage | 65/51 | 18/10 | 22/11 | −5/–11 |

| Juneau | 64/50 | 17/11 | 32/23 | 0/–4 |

| Ketchikan | 64/51 | 17/11 | 38/28 | 3/–1 |

| Unalaska | 57/46 | 14/8 | 36/28 | 2/–2 |

| Fairbanks | 72/53 | 22/11 | 1/–17 | −17/–27 |

| Fort Yukon | 73/51 | 23/10 | −11/–27 | −23/–33 |

| Nome | 58/46 | 14/8 | 13/–2 | −10/–19 |

| Barrow | 47/34 | 8/1 | −7/–19 | −21/–28 |

History

Alaska Natives

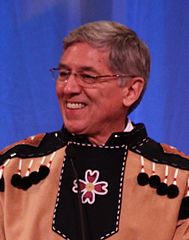

A modern Alutiiq dancer in traditional festival garb.

Numerous indigenous peoples occupied Alaska for thousands of years before the arrival of European peoples to the area. Linguistic and DNA studies done here have provided evidence for the settlement of North America by way of the Bering land bridge.[28] The Tlingit people developed a society with a matrilineal kinship system of property inheritance and descent in what is today Southeast Alaska, along with parts of British Columbia and the Yukon. Also in Southeast were the Haida, now well known for their unique arts. The Tsimshian people came to Alaska from British Columbia in 1887, when President Grover Cleveland, and later the U.S. Congress, granted them permission to settle on Annette Island and found the town of Metlakatla. All three of these peoples, as well as other indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, experienced smallpox outbreaks from the late 18th through the mid-19th century, with the most devastating epidemics occurring in the 1830s and 1860s, resulting in high fatalities and social disruption.[29]

The Aleutian Islands are still home to the Aleut people‘s seafaring society, although they were the first Native Alaskans to be exploited by Russians. Western and Southwestern Alaska are home to the Yup’ik, while their cousins the Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq lived in what is now Southcentral Alaska. The Gwich’in people of the northern Interior region are Athabaskan and primarily known today for their dependence on the caribou within the much-contested Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The North Slope and Little Diomede Island are occupied by the widespread Inupiat people.

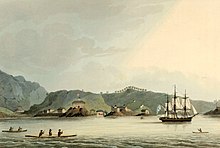

Colonization

Some researchers believe that the first Russian settlement in Alaska was established in the 17th century.[30]According to this hypothesis, in 1648 several koches of Semyon Dezhnyov‘s expedition came ashore in Alaska by storm and founded this settlement. This hypothesis is based on the testimony of Chukchi geographer Nikolai Daurkin, who had visited Alaska in 1764–1765 and who had reported on a village on the Kheuveren River, populated by «bearded men» who «pray to the icons«. Some modern researchers associate Kheuveren with Koyuk River.[31]

The first European vessel to reach Alaska is generally held to be the St. Gabriel under the authority of the surveyor M. S. Gvozdev and assistant navigator I. Fyodorov on August 21, 1732 during an expedition of Siberian cossak A. F. Shestakov and Belorussian explorer Dmitry Pavlutsky (1729—1735).[32]

Another European contact with Alaska occurred in 1741, when Vitus Bering led an expedition for the Russian Navy aboard the St. Peter. After his crew returned to Russia with sea otter pelts judged to be the finest fur in the world, small associations of fur traders began to sail from the shores of Siberia toward the Aleutian Islands. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1784.

The Russian settlement of St. Paul’s Harbor (present-day Kodiak town), Kodiak Island, 1814.

Between 1774 and 1800, Spain sent several expeditions to Alaska in order to assert its claim over the Pacific Northwest. In 1789 a Spanish settlement and fort were built in Nootka Sound. These expeditions gave names to places such as Valdez, Bucareli Sound, and Cordova. Later, the Russian-American Company carried out an expanded colonization program during the early-to-mid-19th century.

Sitka, renamed New Archangel from 1804 to 1867, on Baranof Island in the Alexander Archipelago in what is now Southeast Alaska, became the capital of Russian America. It remained the capital after the colony was transferred to the United States. The Russians never fully colonized Alaska, and the colony was never very profitable. Evidence of Russian settlement in names and churches survive throughout southeast Alaska.

William H. Seward, the United States Secretary of State, negotiated the Alaska Purchase (also known as Seward’s Folly) with the Russians in 1867 for $7.2 million. Alaska was loosely governed by the military initially, and was administered as a district starting in 1884, with a governor appointed by the President of the United States. A federal district court was headquartered in Sitka.

Miners and prospectors climb the Chilkoot Trail during the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush.

For most of Alaska’s first decade under the United States flag, Sitka was the only community inhabited by American settlers. They organized a «provisional city government,» which was Alaska’s first municipal government, but not in a legal sense.[33] Legislation allowing Alaskan communities to legally incorporate as cities did not come about until 1900, and home rule for cities was extremely limited or unavailable until statehood took effect in 1959.

Territory

Starting in the 1890s and stretching in some places to the early 1910s, gold rushes in Alaska and the nearby Yukon Territory brought thousands of miners and settlers to Alaska. Alaska was officially incorporated as an organized territory in 1912. Alaska’s capital, which had been in Sitka until 1906, was moved north to Juneau. Construction of the Alaska Governor’s Mansion began that same year. European immigrants from Norway and Sweden also settled in southeast Alaska, where they entered the fishing and logging industries.

U.S. troops navigate snow and ice during the Battle of Attu in May 1943.

During World War II, the Aleutian Islands Campaign focused on the three outer Aleutian Islands – Attu, Agattu and Kiska[34] – that were invaded by Japanese troops and occupied between June 1942 and August 1943. During the occupation, one Alaskan civilian was killed by Japanese troops and nearly fifty were interned in Japan, where about half of them died. Unalaska/Dutch Harbor became a significant base for the United States Army Air Forces and Navy submariners.

The United States Lend-Lease program involved the flying of American warplanes through Canada to Fairbanks and then Nome; Soviet pilots took possession of these aircraft, ferrying them to fight the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The construction of military bases contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities.

Statehood

Statehood for Alaska was an important cause of James Wickersham early in his tenure as a congressional delegate. Decades later, the statehood movement gained its first real momentum following a territorial referendum in 1946. The Alaska Statehood Committee and Alaska’s Constitutional Convention would soon follow. Statehood supporters also found themselves fighting major battles against political foes, mostly in the U.S. Congress but also within Alaska. Statehood was approved by Congress on July 7, 1958. Alaska was officially proclaimed a state on January 3, 1959.

In 1960, the Census Bureau reported Alaska’s population as 77.2% White, 3% Black, and 18.8% American Indian and Alaska Native.[35]

Kodiak, before and after the tsunami which followed the Good Friday earthquake in 1964, destroying much of the townsite.

Good Friday earthquake

On March 27, 1964, the massive Good Friday earthquake killed 133 people and destroyed several villages and portions of large coastal communities, mainly by the resultant tsunamis and landslides. It was the second-most-powerful earthquake in the recorded history of the world, with a moment magnitude of 9.2. It was over one thousand times more powerful than the 1989 San Francisco earthquake. The time of day (5:36 pm), time of year and location of the epicenter were all cited as factors in potentially sparing thousands of lives, particularly in Anchorage.

Discovery of oil

The 1968 discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay and the 1977 completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System led to an oil boom. Royalty revenues from oil have funded large state budgets from 1980 onward. That same year, not coincidentally, Alaska repealed its state income tax.

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef in the Prince William Sound, spilling over 11 million U.S. gallons (42 megaliters) of crude oil over 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of coastline. Today, the battle between philosophies of development and conservation is seen in the contentious debate over oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the proposed Pebble Mine.

Alaska Heritage Resources Survey

The Alaska Heritage Resources Survey (AHRS) is a restricted inventory of all reported historic and prehistoric sites within the state of Alaska; it is maintained by the Office of History and Archaeology. The survey’s inventory of cultural resources includes objects, structures, buildings, sites, districts, and travel ways, with a general provision that they are over 50 years old. As of January 31, 2012, over 35,000 sites have been reported.[36]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 33,426 | — | |

| 1890 | 32,052 | −4.1% | |

| 1900 | 63,592 | 98.4% | |

| 1910 | 64,356 | 1.2% | |

| 1920 | 55,036 | −14.5% | |

| 1930 | 59,278 | 7.7% | |

| 1940 | 72,524 | 22.3% | |

| 1950 | 128,643 | 77.4% | |

| 1960 | 226,167 | 75.8% | |

| 1970 | 300,382 | 32.8% | |

| 1980 | 401,851 | 33.8% | |

| 1990 | 550,043 | 36.9% | |

| 2000 | 626,932 | 14.0% | |

| 2010 | 710,231 | 13.3% | |

| Est. 2016 | 741,894 | 4.5% | |

| 1930 and 1940 censuses taken in preceding autumn Sources: 1910–2010, US Census Bureau[37] 2016 Estimate[2] |

|||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Alaska was 738,432 on July 1, 2015, a 3.97% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[2]

In 2010, Alaska ranked as the 47th state by population, ahead of North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming (and Washington, D.C.)[2] Alaska is the least densely populated state, and one of the most sparsely populated areas in the world, at 1.2 inhabitants per square mile (0.46/km2), with the next state, Wyoming, at 5.8 inhabitants per square mile (2.2/km2).[38] Alaska is the largest U.S. state by area, and the tenth wealthiest (per capita income).[39] As of November 2014, the state’s unemployment rate was 6.6%.[40]

Race and ancestry

According to the 2010 United States Census, Alaska had a population of 710,231. In terms of race and ethnicity, the state was 66.7% White (64.1% Non-Hispanic White), 14.8% American Indian and Alaska Native, 5.4% Asian, 3.3% Black or African American, 1.0% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 1.6% from Some Other Race, and 7.3% from Two or More Races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 5.5% of the population.[41]

As of 2011, 50.7% of Alaska’s population younger than one year of age belonged to minority groups (i.e., did not have two parents of non-Hispanic white ancestry).[42]

| [hide]Racial composition | 1970[43] | 1990[43] | 2000[44] | 2010[45] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 78.8% | 75.5% | 69.3% | 66.7% |

| Native | 16.9% | 15.6% | 15.6% | 14.8% |

| Asian | 0.9% | 3.6% | 4.0% | 5.4% |

| Black | 3.0% | 4.1% | 3.5% | 3.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.5% | 1.0% |

| Other race | 0.4% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 5.5% | 7.3% |

Languages

According to the 2011 American Community Survey, 83.4% of people over the age of five speak only English at home. About 3.5% speak Spanish at home. About 2.2% speak another Indo-European language at home and about 4.3% speak an Asian language at home.[citation needed]About 5.3% speak other languages at home.[46]

The Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks claims that at least 20 Alaskan native languages exist and there are also some languages with different dialects.[47] Most of Alaska’s native languages belong to either the Eskimo–Aleut or Na-Dene language families however some languages are thought to be isolates (e.g. Haida) or have not yet been classified (e.g. Tsimshianic).[47] As of 2014 nearly all of Alaska’s native languages were classified as either threatened, shifting, moribund, nearly extinct, or dormant languages.[48]

A total of 5.2% of Alaskans speak one of the state’s 20 indigenous languages,[49] known locally as «native languages».

In October 2014, the governor of Alaska signed a bill declaring the state’s 20 indigenous languages as official languages.[50][51] This bill gave the languages symbolic recognition as official languages, though they have not been adopted for official use within the government. The 20 languages that were included in the bill are:

- Inupiaq

- Siberian Yupik

- Central Alaskan Yup’ik

- Alutiiq

- Unangax

- Dena’ina

- Deg Xinag

- Holikachuk

- Koyukon

- Upper Kuskokwim

- Gwich’in

- Tanana

- Upper Tanana

- Tanacross

- Hän

- Ahtna

- Eyak

- Tlingit

- Haida

- Tsimshian

Religion

St. Michael’s Russian Orthodox Cathedral in downtown Sitka.

According to statistics collected by the Association of Religion Data Archives from 2010, about 34% of Alaska residents were members of religious congregations. 100,960 people identified as Evangelical Protestants, 50,866 as Roman Catholic, and 32,550 as mainline Protestants.[52] Roughly 4% are Mormon, 0.5% are Jewish, 1% are Muslim, 0.5% are Buddhist, and 0.5% are Hindu.[53] The largest religious denominations in Alaska as of 2010 were the Catholic Church with 50,866 adherents, non-denominational Evangelical Protestants with 38,070 adherents, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 32,170 adherents, and the Southern Baptist Convention with 19,891 adherents.[54] Alaska has been identified, along with Pacific Northwest states Washington and Oregon, as being the least religious states of the USA, in terms of church membership.[55][56]

In 1795, the First Russian Orthodox Church was established in Kodiak. Intermarriage with Alaskan Natives helped the Russian immigrants integrate into society. As a result, an increasing number of Russian Orthodox churches gradually became established within Alaska.[57] Alaska also has the largest Quaker population (by percentage) of any state.[58] In 2009 there were 6,000 Jews in Alaska (for whom observance of halakha may pose special problems).[59] Alaskan Hindus often share venues and celebrations with members of other Asian religious communities, including Sikhs and Jains.[60][61][62]

Estimates for the number of Muslims in Alaska range from 2,000 to 5,000.[63][64][65] The Islamic Community Center of Anchorage began efforts in the late 1990s to construct a mosque in Anchorage. They broke ground on a building in south Anchorage in 2010 and were nearing completion in late 2014. When completed, the mosque will be the first in the state and one of the northernmost mosques in the world.[66]

| Affiliation | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 62 | |

| Protestant | 37 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 22 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 12 | |

| Black church | 3 | |

| Catholic | 16 | |

| Mormon | 5 | |

| Jehovah’s Witnesses | 0.5 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | |

| Other Christian | 0.5 | |

| Unaffiliated | 31 | |

| Nothing in particular | 20 | |

| Agnostic | 6 | |

| Atheist | 5 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 6 | |

| Jewish | 0.5 | |

| Muslim | 0.5 | |

| Buddhist | 1 | |

| Hindu | 0.5 | |

| Other Non-Christian faiths | 4 | |

| Don’t know/refused answer | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

Economy

Aerial view of infrastructure at the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field.

The 2007 gross state product was $44.9 billion, 45th in the nation. Its per capita personal income for 2007 was $40,042, ranking 15th in the nation. According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Alaska had the fifth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 6.75 percent.[68] The oil and gas industry dominates the Alaskan economy, with more than 80% of the state’s revenues derived from petroleum extraction. Alaska’s main export product (excluding oil and natural gas) is seafood, primarily salmon, cod, Pollock and crab.

Agriculture represents a very small fraction of the Alaskan economy. Agricultural production is primarily for consumption within the state and includes nursery stock, dairy products, vegetables, and livestock. Manufacturing is limited, with most foodstuffs and general goods imported from elsewhere.

Employment is primarily in government and industries such as natural resource extraction, shipping, and transportation. Military bases are a significant component of the economy in the Fairbanks North Star, Anchorage and Kodiak Island boroughs, as well as Kodiak. Federal subsidies are also an important part of the economy, allowing the state to keep taxes low. Its industrial outputs are crude petroleum, natural gas, coal, gold, precious metals, zinc and other mining, seafood processing, timber and wood products. There is also a growing service and tourism sector. Tourists have contributed to the economy by supporting local lodging.

Energy

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline transports oil, Alaska’s most financially important export, from the North Slope to Valdez. Pertinent are the heat pipes in the column mounts, which disperse heat upwards and prevent melting of permafrost.

Alaska has vast energy resources, although its oil reserves have been largely depleted. Major oil and gas reserves were found in the Alaska North Slope (ANS) and Cook Inlet basins, but according to the Energy Information Administration, by February 2014 Alaska had fallen to fourth place in the nation in crude oil production after Texas, North Dakota, and California.[69][70] Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope is still the second highest-yielding oil field in the United States, typically producing about 400,000 barrels per day (64,000 m3/d), although by early 2014 North Dakota’s Bakken Formation was producing over 900,000 barrels per day (140,000 m3/d).[71] Prudhoe Bay was the largest conventional oil field ever discovered in North America, but was much smaller than Canada’s enormous Athabasca oil sands field, which by 2014 was producing about 1,500,000 barrels per day (240,000 m3/d) of unconventional oil, and had hundred

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline can transport and pump up to 2.1 million barrels (330,000 m3) of crude oil per day, more than any other crude oil pipeline in the United States. Additionally, substantial coal deposits are found in Alaska’s bituminous, sub-bituminous, and lignite coal basins. The United States Geological Survey estimates that there are 85.4 trillion cubic feet (2,420 km3) of undiscovered, technically recoverable gas from natural gas hydrates on the Alaskan North Slope.[73] Alaska also offers some of the highest hydroelectric power potential in the country from its numerous rivers. Large swaths of the Alaskan coastline offer wind and geothermal energy potential as well.[74]

Alaska’s economy depends heavily on increasingly expensive diesel fuel for heating, transportation, electric power and light. Though wind and hydroelectric power are abundant and underdeveloped, proposals for statewide energy systems (e.g. with special low-cost electric interties) were judged uneconomical (at the time of the report, 2001) due to low (less than 50¢/gal) fuel prices, long distances and low population.[75]The cost of a gallon of gas in urban Alaska today is usually 30–60¢ higher than the national average; prices in rural areas are generally significantly higher but vary widely depending on transportation costs, seasonal usage peaks, nearby petroleum development infrastructure and many other factors.

Permanent Fund

The Alaska Permanent Fund is a constitutionally authorized appropriation of oil revenues, established by voters in 1976 to manage a surplus in state petroleum revenues from oil, largely in anticipation of the then recently constructed Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. The fund was originally proposed by Governor Keith Miller on the eve of the 1969 Prudhoe Bay lease sale, out of fear that the legislature would spend the entire proceeds of the sale (which amounted to $900 million) at once. It was later championed by Governor Jay Hammond and Kenaistate representative Hugh Malone. It has served as an attractive political prospect ever since, diverting revenues which would normally be deposited into the general fund.

The Alaska Constitution was written so as to discourage dedicating state funds for a particular purpose. The Permanent Fund has become the rare exception to this, mostly due to the political climate of distrust existing during the time of its creation. From its initial principal of $734,000, the fund has grown to $50 billion as a result of oil royalties and capital investment programs.[76] Most if not all the principal is invested conservatively outside Alaska. This has led to frequent calls by Alaskan politicians for the Fund to make investments within Alaska, though such a stance has never gained momentum.

Starting in 1982, dividends from the fund’s annual growth have been paid out each year to eligible Alaskans, ranging from an initial $1,000 in 1982 (equal to three years’ payout, as the distribution of payments was held up in a lawsuit over the distribution scheme) to $3,269 in 2008 (which included a one-time $1,200 «Resource Rebate»). Every year, the state legislature takes out 8% from the earnings, puts 3% back into the principal for inflation proofing, and the remaining 5% is distributed to all qualifying Alaskans. To qualify for the Permanent Fund Dividend, one must have lived in the state for a minimum of 12 months, maintain constant residency subject to allowable absences,[77] and not be subject to court judgments or criminal convictions which fall under various disqualifying classifications or may subject the payment amount to civil garnishment.

The Permanent Fund is often considered to be one of the leading examples of a «Basic Income» policy in the world.[78]

Cost of living

The cost of goods in Alaska has long been higher than in the contiguous 48 states. Federal government employees, particularly United States Postal Service (USPS) workers and active-duty military members, receive a Cost of Living Allowance usually set at 25% of base pay because, while the cost of living has gone down, it is still one of the highest in the country.[citation needed]

Rural Alaska suffers from extremely high prices for food and consumer goods compared to the rest of the country, due to the relatively limited transportation infrastructure.[citation needed]

Agriculture and fishing

Halibut is important to the state’s economy as both a commercial and sport-caught fish.

Due to the northern climate and short growing season, relatively little farming occurs in Alaska. Most farms are in either the Matanuska Valley, about 40 miles (64 km) northeast of Anchorage, or on the Kenai Peninsula, about 60 miles (97 km) southwest of Anchorage. The short 100-day growing season limits the crops that can be grown, but the long sunny summer days make for productive growing seasons. The primary crops are potatoes, carrots, lettuce, and cabbage.

The Tanana Valley is another notable agricultural locus, especially the Delta Junction area, about 100 miles (160 km) southeast of Fairbanks, with a sizable concentration of farms growing agronomic crops; these farms mostly lie north and east of Fort Greely. This area was largely set aside and developed under a state program spearheaded by Hammond during his second term as governor. Delta-area crops consist predominately of barley and hay. West of Fairbanks lies another concentration of small farms catering to restaurants, the hotel and tourist industry, and community-supported agriculture.

Alaskan agriculture has experienced a surge in growth of market gardeners, small farms and farmers’ markets in recent years, with the highest percentage increase (46%) in the nation in growth in farmers’ markets in 2011, compared to 17% nationwide.[79] The peony industry has also taken off, as the growing season allows farmers to harvest during a gap in supply elsewhere in the world, thereby filling a niche in the flower market.[80]

Alaska, with no counties, lacks county fairs. However, a small assortment of state and local fairs (with the Alaska State Fair in Palmer the largest), are held mostly in the late summer. The fairs are mostly located in communities with historic or current agricultural activity, and feature local farmers exhibiting produce in addition to more high-profile commercial activities such as carnival rides, concerts and food. «Alaska Grown» is used as an agricultural slogan.

Alaska has an abundance of seafood, with the primary fisheries in the Bering Sea and the North Pacific. Seafood is one of the few food items that is often cheaper within the state than outside it. Many Alaskans take advantage of salmon seasons to harvest portions of their household diet while fishing for subsistence, as well as sport. This includes fish taken by hook, net or wheel.[81]

Hunting for subsistence, primarily caribou, moose, and Dall sheep is still common in the state, particularly in remote Bush communities. An example of a traditional native food is Akutaq, the Eskimo ice cream, which can consist of reindeer fat, seal oil, dried fish meat and local berries.

Alaska’s reindeer herding is concentrated on Seward Peninsula, where wild caribou can be prevented from mingling and migrating with the domesticated reindeer.[82]

Most food in Alaska is transported into the state from «Outside», and shipping costs make food in the cities relatively expensive. In rural areas, subsistence hunting and gathering is an essential activity because imported food is prohibitively expensive. Though most small towns and villages in Alaska lie along the coastline, the cost of importing food to remote villages can be high, because of the terrain and difficult road conditions, which change dramatically, due to varying climate and precipitation changes. The cost of transport can reach as high as 50¢ per pound ($1.10/kg) or more in some remote areas, during the most difficult times, if these locations can be reached at all during such inclement weather and terrain conditions. The cost of delivering a 1 US gallon (3.8 L) of milk is about $3.50 in many villages where per capita income can be $20,000 or less. Fuel cost per gallon is routinely 20–30¢ higher than the continental United States average, with only Hawaii having higher prices.[83][ 84]

84]

Transportation

The Sterling Highway, near its intersection with the Seward Highway.

Roads

The Susitna River bridge on the Denali Highway is 1,036 feet (316 m) long.

Alaska has few road connections compared to the rest of the U.S. The state’s road system covers a relatively small area of the state, linking the central population centers and the Alaska Highway, the principal route out of the state through Canada. The state capital, Juneau, is not accessible by road, only a car ferry, which has spurred several debates over the decades about moving the capital to a city on the road system, or building a road connection from Haines. The western part of Alaska has no road system connecting the communities with the rest of Alaska.

One unique feature of the Alaska Highway system is the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel, an active Alaska Railroad tunnel recently upgraded to provide a paved roadway link with the isolated community of Whittier on Prince William Sound to the Seward Highway about 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Anchorage at Portage. At 2.5 miles (4.0 km), the tunnel was the longest road tunnel in North America until 2007.[85] The tunnel is the longest combination road and rail tunnel in North America.

Rail

An Alaska Railroad locomotive and tanker cars crossing the George Parks Highway in 1994.

The White Pass and Yukon Route traverses rugged terrain north of Skagway near the Canada–US border.

Built around 1915, the Alaska Railroad (ARR) played a key role in the development of Alaska through the 20th century. It links north Pacific shipping through providing critical infrastructure with tracks that run from Seward to Interior Alaska by way of South Central Alaska, passing through Anchorage, Eklutna, Wasilla, Talkeetna, Denali, and Fairbanks, with spurs to Whittier, Palmer and North Pole. The cities, towns, villages, and region served by ARR tracks are known statewide as «The Railbelt». In recent years, the ever-improving paved highway system began to eclipse the railroad’s importance in Alaska’s economy.

The railroad played a vital role in Alaska’s development, moving freight into Alaska while transporting natural resources southward (i.e., coal from the Usibelli coal mine near Healy to Seward and gravel from the Matanuska Valley to Anchorage). It is well known for its summertime tour passenger service.

The Alaska Railroad was one of the last railroads in North America to use cabooses in regular service and still uses them on some gravel trains. It continues to offer one of the last flag stop routes in the country. A stretch of about 60 miles (100 km) of track along an area north of Talkeetna remains inaccessible by road; the railroad provides the only transportation to rural homes and cabins in the area. Until construction of the Parks Highway in the 1970s, the railroad provided the only land access to most of the region along its entire route.

In northern Southeast Alaska, the White Pass and Yukon Route also partly runs through the state from Skagway northwards into Canada (British Columbia and Yukon Territory), crossing the border at White Pass Summit. This line is now mainly used by tourists, often arriving by cruise liner at Skagway. It was featured in the 1983 BBC television series Great Little Railways.

The Alaska Rail network is not connected to Outside. In 2000, the U.S. Congress authorized $6 million to study the feasibility of a rail link between Alaska, Canada, and the lower 48.[86][87][88]

Alaska Rail Marine provides car float service between Whittier and Seattle.

Marine transport

Many cities, towns and villages in the state do not have road or highway access; the only modes of access involve travel by air, river, or the sea.

The MV Tustumena (named after Tustumena Glacier) is one of the state’s many ferries, providing service between the Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Island and the Aleutian Chain.

Alaska’s well-developed state-owned ferry system (known as the Alaska Marine Highway) serves the cities of southeast, the Gulf Coast and the Alaska Peninsula. The ferries transport vehicles as well as passengers. The system also operates a ferry service from Bellingham, Washington and Prince Rupert, British Columbia in Canada through the Inside Passage to Skagway. The Inter-Island Ferry Authority also serves as an important marine link for many communities in the Prince of Wales Island region of Southeast and works in concert with the Alaska Marine Highway.

In recent years, cruise lines have created a summertime tourism market, mainly connecting the Pacific Northwest to Southeast Alaska and, to a lesser degree, towns along Alaska’s gulf coast. The population of Ketchikan may rise by over 10,000 people on many days during the summer, as up to four large cruise ships at a time can dock, debarking thousands of passengers.

Air transport

Cities not served by road, sea, or river can be reached only by air, foot, dogsled, or snowmachine, accounting for Alaska’s extremely well developed bush air services—an Alaskan novelty. Anchorage and, to a lesser extent Fairbanks, is served by many major airlines. Because of limited highway access, air travel remains the most efficient form of transportation in and out of the state. Anchorage recently completed extensive remodeling and construction at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport to help accommodate the upsurge in tourism (in 2012–2013, Alaska received almost 2 million visitors).[89]

Regular flights to most villages and towns within the state that are commercially viable are challenging to provide, so they are heavily subsidized by the federal government through the Essential Air Service program. Alaska Airlines is the only major airline offering in-state travel with jet service (sometimes in combination cargo and passenger Boeing 737-400s) from Anchorage and Fairbanks to regional hubs like Bethel, Nome, Kotzebue, Dillingham, Kodiak, and other larger communities as well as to major Southeast and Alaska Peninsula communities.

A Bombardier Dash 8, operated by Era Alaska, on approach to Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport.

The bulk of remaining commercial flight offerings come from small regional commuter airlines such as Ravn Alaska, PenAir, and Frontier Flying Service. The smallest towns and villages must rely on scheduled or chartered bush flying services using general aviation aircraft such as the Cessna Caravan, the most popular aircraft in use in the state. Much of this service can be attributed to the Alaska bypass mail program which subsidizes bulk mail delivery to Alaskan rural communities. The program requires 70% of that subsidy to go to carriers who offer passenger service to the communities.

Many communities have small air taxi services. These operations originated from the demand for customized transport to remote areas. Perhaps the most quintessentially Alaskan plane is the bush seaplane. The world’s busiest seaplane base is Lake Hood, located next to Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, where flights bound for remote villages without an airstrip carry passengers, cargo, and many items from stores and warehouse clubs. In 2006 Alaska had the highest number of pilots per capita of any U.S. state.[90]

Other transport

Another Alaskan transportation method is the dogsled. In modern times (that is, any time after the mid-late 1920s), dog mushing is more of a sport than a true means of transportation. Various races are held around the state, but the best known is the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, a 1,150-mile (1,850 km) trail from Anchorage to Nome (although the distance varies from year to year, the official distance is set at 1,049 miles or 1,688 km). The race commemorates the famous 1925 serum run to Nome in which mushers and dogs like Togo and Balto took much-needed medicine to the diphtheria-stricken community of Nome when all other means of transportation had failed. Mushers from all over the world come to Anchorage each March to compete for cash, prizes, and prestige. The «Serum Run» is another sled dog race that more accurately follows the route of the famous 1925 relay, leaving from the community of Nenana (southwest of Fairbanks) to Nome.[91]

In areas not served by road or rail, primary transportation in summer is by all-terrain vehicle and in winter by snowmobile or «snow machine,» as it is commonly referred to in Alaska.

Data transport

Alaska’s internet and other data transport systems are provided largely through the two major telecommunications companies: GCI and Alaska Communications. GCI owns and operates what it calls the Alaska United Fiber Optic system[92] and as of late 2011 Alaska Communications advertised that it has «two fiber optic paths to the lower 48 and two more across Alaska.[93] In January 2011, it was reported that a $1 billion project to connect Asia and rural Alaska was being planned, aided in part by $350 million in stimulus from the federal government.[94]

Law and government

State government

The center of state government in Juneau. The large buildings in the background are, from left to right: the Court Plaza Building (known colloquially as the «Spam Can«), the State Office Building (behind), the Alaska Office Building, the John H. Dimond State Courthouse, and the Alaska State Capitol. Many of the smaller buildings in the foreground are also occupied by state government agencies.

Like all other U.S. states, Alaska is governed as a republic, with three branches of government: an executive branch consisting of the Governor of Alaska and the other independently elected constitutional officers; a legislative branch consisting of the Alaska House of Representatives and Alaska Senate; and a judicial branch consisting of the Alaska Supreme Court and lower courts.

The state of Alaska employs approximately 16,000 people statewide.[95]

The Alaska Legislature consists of a 40-member House of Representatives and a 20-member Senate. Senators serve four-year terms and House members two. The Governor of Alaska serves four-year terms. The lieutenant governor runs separately from the governor in the primaries, but during the general election, the nominee for governor and nominee for lieutenant governor run together on the same ticket.

Alaska’s court system has four levels: the Alaska Supreme Court, the Alaska Court of Appeals, the superior courts and the district courts.[96] The superior and district courts are trial courts. Superior courts are courts of general jurisdiction, while district courts only hear certain types of cases, including misdemeanor criminal cases and civil cases valued up to $100,000.[96]

The Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals are appellate courts. The Court of Appeals is required to hear appeals from certain lower-court decisions, including those regarding criminal prosecutions, juvenile delinquency, and habeas corpus.[96] The Supreme Court hears civil appeals and may in its discretion hear criminal appeals.[96]

State politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | 39.4% 19,299 | 59.6% 29,189 |

| 1962 | 47.7% 27,054 | 52.3% 29,627 |

| 1966 | 50.0% 33,145 | 48.4% 32,065 |

| 1970 | 46.1% 37,264 | 52.4% 42,309 |

| 1974 | 47.7% 45,840 | 47.4% 45,553 |

| 1978 | 39.1% 49,580 | 20.2% 25,656 |

| 1982 | 37.1% 72,291 | 46.1% 89,918 |

| 1986 | 42.6% 76,515 | 47.3% 84,943 |

| 1990 | 26.2% 50,991 | 30.9% 60,201 |

| 1994 | 40.8% 87,157 | 41.1% 87,693 |

| 1998 | 17.9% 39,331 | 51.3% 112,879 |

| 2002 | 55.9% 129,279 | 40.7% 94,216 |

| 2006 | 48.3% 114,697 | 41.0% 97,238 |

| 2010 | 59.1% 151,318 | 37.7% 96,519 |

| 2014 | 45.9% 128,435 | [a] |

Although in its early years of statehood Alaska was a Democratic state, since the early 1970s it has been characterized as Republican-leaning.[98] Local political communities have often worked on issues related to land use development, fishing, tourism, and individual rights. Alaska Natives, while organized in and around their communities, have been active within the Native corporations. These have been given ownership over large tracts of land, which require stewardship.

Alaska was formerly the only state in which possession of one ounce or less of marijuana in one’s home was completely legal under state law, though the federal law remains in force.[99]

The state has an independence movement favoring a vote on secession from the United States, with the Alaskan Independence Party.[100]

Six Republicans and four Democrats have served as governor of Alaska. In addition, Republican Governor Wally Hickel was elected to the office for a second term in 1990 after leaving the Republican party and briefly joining the Alaskan Independence Party ticket just long enough to be reelected. He officially rejoined the Republican party in 1994.

Alaska’s voter initiative making marijuana legal took effect 24 February 2015, placing Alaska alongside Colorado and Washington as the first three U.S. states where recreational marijuana is legal. The new law means people over age 21 can consume small amounts of pot — if they can find it. There is a rather lengthy and involved application process, per Alaska Measure 2 (2014).[101] The first legal marijuana store opened in Valdez in October 2016.[102]

Taxes

To finance state government operations, Alaska depends primarily on petroleum revenues and federal subsidies. This allows it to have the lowest individual tax burden in the United States.[103] It is one of five states with no state sales tax, one of seven states that do not levy an individual income tax, and one of the two states that has neither. The Department of Revenue Tax Division[104] reports regularly on the state’s revenue sources. The Department also issues an annual summary of its operations, including new state laws that directly affect the tax division.

While Alaska has no state sales tax, 89 municipalities collect a local sales tax, from 1.0–7.5%, typically 3–5%. Other local taxes levied include raw fish taxes, hotel, motel, and bed-and-breakfast ‘bed’ taxes, severance taxes, liquor and tobacco taxes, gaming (pull tabs) taxes, tire taxes and fuel transfer taxes. A part of the revenue collected from certain state taxes and license fees (such as petroleum, aviation motor fuel, telephone cooperative) is shared with municipalities in Alaska.

Fairbanks has one of the highest property taxes in the state as no sales or income taxes are assessed in the Fairbanks North Star Borough (FNSB). A sales tax for the FNSB has been voted on many times, but has yet to be approved, leading lawmakers to increase taxes dramatically on goods such as liquor and tobacco.

In 2014 the Tax Foundation ranked Alaska as having the fourth most «business friendly» tax policy, behind only Wyoming, South Dakota, and Nevada.[105]

Federal politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 50.9% 30,953 | 49.1% 29,809 |

| 1964 | 34.1% 22,930 | 65.9% 44,329 |

| 1968 | 45.3% 37,600 | 42.7% 35,411 |

| 1972 | 58.1% 55,349 | 34.6% 32,967 |

| 1976 | 57.9% 71,555 | 35.7% 44,058 |

| 1980 | 54.4% 86,112 | 26.4% 41,842 |

| 1984 | 66.7% 138,377 | 29.9% 62,007 |

| 1988 | 59.6% 119,251 | 36.3% 72,584 |

| 1992 | 39.5% 102,000 | 30.3% 78,294 |

| 1996 | 50.8% 122,746 | 33.3% 80,380 |

| 2000 | 58.6% 167,398 | 27.7% 79,004 |

| 2004 | 61.1% 190,889 | 35.5% 111,025 |

| 2008 | 59.4% 193,841 | 37.8% 123,594 |

| 2012 | 54.8% 164,676 | 40.8% 122,640 |

| 2016 | 51.3% 163,387 | 36.6% 116,454 |

Alaska regularly supports Republicans in presidential elections and has done so since statehood. Republicans have won the state’s electoral college votes in all but one election that it has participated in (1964). No state has voted for a Democratic presidential candidate fewer times. Alaska was carried by Democratic nominee Lyndon B. Johnson during his landslide election in 1964, while the 1960 and 1968 elections were close. Since 1972, however, Republicans have carried the state by large margins. In 2008, Republican John McCain defeated Democrat Barack Obama in Alaska, 59.49% to 37.83%. McCain’s running mate was Sarah Palin, the state’s governor and the first Alaskan on a major party ticket. Obama lost Alaska again in 2012, but he captured 40% of the state’s vote in that election, making him the first Democrat to do so since 1968.

The Alaska Bush, central Juneau, midtown and downtown Anchorage, and the areas surrounding the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus and Ester have been strongholds of the Democratic Party. The Matanuska-Susitna Borough, the majority of Fairbanks (including North Pole and the military base), and South Anchorage typically have the strongest Republican showing. As of 2004, well over half of all registered voters have chosen «Non-Partisan» or «Undeclared» as their affiliation,[106]despite recent attempts to close primaries to unaffiliated voters.

Because of its population relative to other U.S. states, Alaska has only one member in the U.S. House of Representatives. This seat is held by Republican Don Young, who was re-elected to his 21st consecutive term in 2012. Alaska’s at-large congressional district is one of the largest parliamentary constituencies in the world.

In 2008, Governor Sarah Palin became the first Republican woman to run on a national ticket when she became John McCain‘s running mate. She continued to be a prominent national figure even after resigning from the governor’s job in July 2009.[107]

Alaska’s United States Senators belong to Class 2 and Class 3. In 2008, Democrat Mark Begich, mayor of Anchorage, defeated long-time Republican senator Ted Stevens. Stevens had been convicted on seven felony counts of failing to report gifts on Senate financial discloser forms one week before the election. The conviction was set aside in April 2009 after evidence of prosecutorial misconduct emerged.

Republican Frank Murkowski held the state’s other senatorial position. After being elected governor in 2002, he resigned from the Senate and appointed his daughter, State Representative Lisa Murkowski as his successor. She won full six-year terms in 2004 and 2010.

- Alaska’s current statewide elected officials

-

Lisa Murkowski, senior United States Senator

-

Dan Sullivan, junior United States Senator

Cities, towns and boroughs

Anchorage, Alaska, Alaska’s largest city.

Fairbanks, Alaska’s second-largest city and by a significant margin the largest city in Alaska’s interior.

Juneau, Alaska’s third-largest city and its capital.

Bethel, the largest city in the Unorganized Borough and in rural Alaska.

Homer, showing (from bottom to top) the edge of downtown, its airport and the Spit.

Barrow (Browerville neighborhood near Eben Hopson Middle School shown), known colloquially for many years by the nickname «Top of the World», is the northernmost city in the United States.

Cordova, built in the early 20th century to support the Kennecott Mines and the Copper River and Northwestern Railway, has persevered as a fishing community since their closure.

Main Street in Talkeetna.

Alaska is not divided into counties, as most of the other U.S. states, but it is divided into boroughs.[108] Many of the more densely populated parts of the state are part of Alaska’s 16 boroughs, which function somewhat similarly to counties in other states. However, unlike county-equivalents in the other 49 states, the boroughs do not cover the entire land area of the state. The area not part of any borough is referred to as the Unorganized Borough.

The Unorganized Borough has no government of its own, but the U.S. Census Bureau in cooperation with the state divided the Unorganized Borough into 11 census areas solely for the purposes of statistical analysis and presentation.[citation needed] A recording district is a mechanism for administration of the public record in Alaska. The state is divided into 34 recording districts which are centrally administered under a State Recorder. All recording districts use the same acceptance criteria, fee schedule, etc., for accepting documents into the public record.[citation needed]

Whereas many U.S. states use a three-tiered system of decentralization—state/county/township—most of Alaska uses only two tiers—state/borough. Owing to the low population density, most of the land is located in the Unorganized Borough. As the name implies, it has no intermediate borough government but is administered directly by the state government. In 2000, 57.71% of Alaska’s area has this status, with 13.05% of the population.[citation needed]

Anchorage merged the city government with the Greater Anchorage Area Borough in 1975 to form the Municipality of Anchorage, containing the city proper and the communities of Eagle River, Chugiak, Peters Creek, Girdwood, Bird, and Indian. Fairbanks has a separate borough (the Fairbanks North Star Borough) and municipality (the City of Fairbanks).[citation needed]

The state’s most populous city is Anchorage, home to 278,700 people in 2006, 225,744 of whom live in the urbanized area. The richest location in Alaska by per capita income is Halibut Cove ($89,895).[citation needed]Yakutat City, Sitka, Juneau, and Anchorage are the four largest cities in the U.S. by area.

Cities and census-designated places (by population)

As reflected in the 2010 United States Census, Alaska has a total of 355 incorporated cities and census-designated places (CDPs).[citation needed] The tally of cities includes four unified municipalities, essentially the equivalent of a consolidated city–county. The majority of these communities are located in the rural expanse of Alaska known as «The Bush» and are unconnected to the contiguous North American road network. The table at the bottom of this section lists the 100 largest cities and census-designated places in Alaska, in population order.

Of Alaska’s 2010 Census population figure of 710,231, 20,429 people, or 2.88% of the population, did not live in an incorporated city or census-designated place. Approximately three-quarters of that figure were people who live in urban and suburban neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city limits of Ketchikan, Kodiak, Palmer and Wasilla.[citation needed] CDPs have not been established for these areas by the United States Census Bureau, except that seven CDPs were established for the Ketchikan-area neighborhoods in the 1980 Census (Clover Pass, Herring Cove, Ketchikan East, Mountain Point, North Tongass Highway, Pennock Island and Saxman East), but have not been used since. The remaining population was scattered throughout Alaska, both within organized boroughs and in the Unorganized Borough, in largely remote areas.[citation needed]

|

|

Education

The Kachemak Bay Campus of the University of Alaska Anchorage, located in downtown Homer.

The Alaska Department of Education and Early Development administers many school districts in Alaska. In addition, the state operates a boarding school, Mt. Edgecumbe High School in Sitka, and provides partial funding for other boarding schools, including Nenana Student Living Center in Nenana and The Galena Interior Learning Academy in Galena.[109]

There are more than a dozen colleges and universities in Alaska. Accredited universities in Alaska include the University of Alaska Anchorage, University of Alaska Fairbanks, University of Alaska Southeast, and Alaska Pacific University.[110] Alaska is the only state that has no institutions that are part of the NCAA Division I.

The Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development operates AVTEC, Alaska’s Institute of Technology.[111] Campuses in Seward and Anchorage offer 1 week to 11-month training programs in areas as diverse as Information Technology, Welding, Nursing, and Mechanics.

Alaska has had a problem with a «brain drain«. Many of its young people, including most of the highest academic achievers, leave the state after high school graduation and do not return. As of 2013, Alaska did not have a law school or medical school.[112] The University of Alaska has attempted to combat this by offering partial four-year scholarships to the top 10% of Alaska high school graduates, via the Alaska Scholars Program.[113]

Public health and public safety

The Alaska State Troopers are Alaska’s statewide police force. They have a long and storied history, but were not an official organization until 1941. Before the force was officially organized, law enforcement in Alaska was handled by various federal agencies. Larger towns usually have their own local police and some villages rely on «Public Safety Officers» who have police training but do not carry firearms. In much of the state, the troopers serve as the only police force available. In addition to enforcing traffic and criminal law, wildlife Troopers enforce hunting and fishing regulations. Due to the varied terrain and wide scope of the Troopers’ duties, they employ a wide variety of land, air, and water patrol vehicles.

Many rural communities in Alaska are considered «dry,» having outlawed the importation of alcoholic beverages.[114] Suicide rates for rural residents are higher than urban.[115]

Domestic abuse and other violent crimes are also at high levels in the state; this is in part linked to alcohol abuse.[116] Alaska has the highest rate of sexual assault in the nation, especially in rural areas. The average age of sexually assaulted victims is 16 years old. In four out of five cases, the suspects were relatives, friends or acquaintances.[117]

Culture

A dog team in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, arguably the most popular winter event in Alaska.

Some of Alaska’s popular annual events are the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race that starts in Anchorage and ends in Nome, World Ice Art Championships in Fairbanks, the Blueberry Festival and Alaska Hummingbird Festival in Ketchikan, the Sitka Whale Fest, and the Stikine River Garnet Fest in Wrangell. The Stikine River attracts the largest springtime concentration of American bald eagles in the world.

The Alaska Native Heritage Center celebrates the rich heritage of Alaska’s 11 cultural groups. Their purpose is to encourage cross-cultural exchanges among all people and enhance self-esteem among Native people. The Alaska Native Arts Foundation promotes and markets Native art from all regions and cultures in the State, using the internet.[118]

Music

Influences on music in Alaska include the traditional music of Alaska Natives as well as folk music brought by later immigrants from Russia and Europe. Prominent musicians from Alaska include singer Jewel, traditional Aleut flautist Mary Youngblood, folk singer-songwriter Libby Roderick, Christian music singer-songwriter Lincoln Brewster, metal/post hardcore band 36 Crazyfists and the groups Pamyua and Portugal. The Man.

There are many established music festivals in Alaska, including the Alaska Folk Festival, the Fairbanks Summer Arts Festival, the Anchorage Folk Festival, the Athabascan Old-Time Fiddling Festival, the Sitka Jazz Festival, and the Sitka Summer Music Festival. The most prominent orchestra in Alaska is the Anchorage Symphony Orchestra, though the Fairbanks Symphony Orchestra and Juneau Symphony are also notable. The Anchorage Opera is currently the state’s only professional opera company, though there are several volunteer and semi-professional organizations in the state as well.

The official state song of Alaska is «Alaska’s Flag«, which was adopted in 1955; it celebrates the flag of Alaska.

Alaska in film and on television

Films featuring Alaskan wolves usually employ domesticated wolf-dog hybrids to stand in for wild wolves.

Alaska’s first independent picture entirely made in Alaska was The Chechahcos, produced by Alaskan businessman Austin E. Lathrop and filmed in and around Anchorage. Released in 1924 by the Alaska Moving Picture Corporation, it was the only film the company made.

One of the most prominent movies filmed in Alaska is MGM‘s Eskimo/Mala The Magnificent, starring Alaska Native Ray Mala. In 1932 an expedition set out from MGM‘s studios in Hollywood to Alaska to film what was then billed as «The Biggest Picture Ever Made.» Upon arriving in Alaska, they set up «Camp Hollywood» in Northwest Alaska, where they lived during the duration of the filming. Louis B. Mayer spared no expense in spite of the remote location, going so far as to hire the chef from the Hotel Roosevelt in Hollywood to prepare meals.

When Eskimo premiered at the Astor Theatre in New York City, the studio received the largest amount of feedback in its history to that point. Eskimo was critically acclaimed and released worldwide; as a result, Mala became an international movie star. Eskimo won the first Oscar for Best Film Editing at the Academy Awards, and showcased and preserved aspects of Inupiat culture on film.

The 1983 Disney movie Never Cry Wolf was at least partially shot in Alaska. The 1991 film White Fang, based on Jack London‘s novel and starring Ethan Hawke, was filmed in and around Haines. Steven Seagal‘s 1994 On Deadly Ground, starring Michael Caine, was filmed in part at the Worthington Glacier near Valdez.[119] The 1999 John Sayles film Limbo, starring David Strathairn, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, and Kris Kristofferson, was filmed in Juneau.

The psychological thriller Insomnia, starring Al Pacino and Robin Williams, was shot in Canada, but was set in Alaska. The 2007 film directed by Sean Penn, Into The Wild, was partially filmed and set in Alaska. The film, which is based on the novel of the same name, follows the adventures of Christopher McCandless, who died in a remote abandoned bus along the Stampede Trail west of Healy in 1992.

Many films and television shows set in Alaska are not filmed there; for example, Northern Exposure, set in the fictional town of Cicely, Alaska, was filmed in Roslyn, Washington. The 2007 horror feature 30 Days of Night is set in Barrow, but was filmed in New Zealand.

Many reality television shows are filmed in Alaska. In 2011 the Anchorage Daily News found ten set in the state.[120]

State symbols

The forget-me-not is the state’s official flower and bears the same blue and gold as the state flag.

- State motto: North to the Future

- Nicknames: «The Last Frontier» or «Land of the Midnight Sun» or «Seward’s Icebox»

- State bird: willow ptarmigan, adopted by the Territorial Legislature in 1955. It is a small (15–17 in or 380–430 mm) Arctic grouse that lives among willows and on open tundra and muskeg. Plumage is brown in summer, changing to white in winter. The willow ptarmigan is common in much of Alaska.

- State fish: king salmon, adopted 1962.

- State flower: wild/native forget-me-not, adopted by the Territorial Legislature in 1917.[121] It is a perennial that is found throughout Alaska, from Hyder to the Arctic Coast, and west to the Aleutians.

- State fossil: woolly mammoth, adopted 1986.

- State gem: jade, adopted 1968.

- State insect: four-spot skimmer dragonfly, adopted 1995.

- State land mammal: moose, adopted 1998.

- State marine mammal: bowhead whale, adopted 1983.

- State mineral: gold, adopted 1968.

- State song: «Alaska’s Flag«

- State sport: dog mushing, adopted 1972.

- State tree: Sitka spruce, adopted 1962.

- State dog: Alaskan Malamute, adopted 2010.[122]